|

|---|

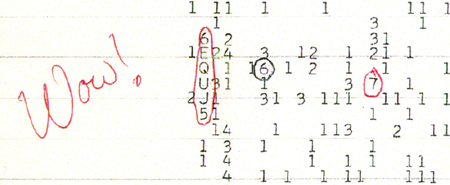

| The code "6EQUJ5" indicates a radio signal detected in 1977 at the Big Ear Radio Observatory in Ohio - a signal so strong that astronomer Jerry Ehman wrote "Wow!" |

|

The "Wow" Mystery Turns 30

MSNBC

August 21, 2007

Area: Columbus, OH

Exactly 30 years ago today, astronomer Jerry Ehman was looking over a printout of radio data from Ohio State University's Big Ear Radio Observatory when he saw a string of code so remarkable that he had to circle it and scribble "Wow!" in the margin. The printout recorded an anomalous signal so strong that it had to come from an extraordinary source.

Was it a burst of human-made interference? Or an alien broadcast from the stars? No one knows. The source of the "Wow" signal has never been heard from again - even though astronomers have looked for it dozens of times.

Now the SETI Institute is gearing up to look for it one more time, using the latest tool for seeking signals from extraterrestrial civilizations: the Allen Telescope Array in California.

The array combines observations from dozens of separate 20-foot-wide (6-meter-wide) radio dishes to produce an instrument that will eventually become more sensitive than the world's largest single-dish telescope, the Arecibo Observatory.

"Once the Allen Telescope Array is up and running, and that should be later this year, there's going to be a small project in which we'll look at the same section where the 'Wow' signal was detected, and of course the same spot on the radio dial," Seth Shostak, senior astronomer at the SETI Institute, told me today.

Although that area of the sky has been searched dozens of times before, the Allen Telescope Array will bring more sensitivity and wider spectral coverage to the quest, Shostak said.

The renewed search came as welcome news to Ehman, the man behind the "Wow."

"Back in 1977, of course, the computers weren't very powerful," he told me. "Nowadays, if you have the money, you can get excellent receivers, filter banks, computers - you can do much more now than you could in 1977."

But he cautioned that the search could well come up empty again.

"With the Big Ear Radio Telescope, we stayed on that same strip of sky for close to two months and didn't see anything," he said. "A few years later, we looked at that same area of sky and didn't see anything. That was frustrating."

After the single radio burst was detected, astronomers tried to track down a terrestrial cause. But they could find no glitch in the system, and no source that could have explained the strength and the frequency of the seconds-long signal. Since then, the "Wow" signal has stood as one of the central enigmas for alien-hunters, inspiring a scene in "The X-Files."

"The 'Wow' signal is the best evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence," says one character, who refers to Ehman as "my buddy."

Ehman said aliens weren't the first thing that came to his mind when he saw the Big Ear data and wrote his famous word.

"The 'Wow' was just an instantaneous response in writing," he said. "I had no expectations, other than 'here's something extremely interesting - and gee, let's try to find out what it is, or what it isn't.'"

Ehman recently updated his own report on the "Wow" signal for the 30th anniversary, but the report's conclusion hasn't changed over all this time.

"It's still an open question what the source of the signal was," he told me. "We just don't have enough information to determine that. ... We just can't draw any conclusion other than it still allows for the possibility that it was a signal from an extraterrestrial civilization."

Over the past three decades, signal searchers have developed strategies for dealing with "Wow"-type anomalies, Shostak said. For example, if an interesting signal happens to be on a precisely tuned frequency like 14.2700000 MHz, Shostak said it's safe to assume that "some earthly engineer" is responsible (unless E.T. also uses a decimal counting system and measures time in earthly seconds).

If astronomers pick up an interesting signal from one point in the sky, they'll shift their telescope's focus to aim at a different spot. If the signal doesn't go away, the astronomers assume that terrestrial interference is affecting the observations.

That kind of reality check will be much easier to do with the Allen Telescope Array, Shostak said. "You can very quickly switch the telescope to 'point' in a different direction without physically moving the antenna," he said.

For these reasons, the modern search for extraterrestrial intelligence hasn't produced a fresh crop of "Wow" signals, although every once in a while there's a false alarm that sets Shostak's heart racing.

It could well be that the "Wow" signal will remain in a class by itself for millennia to come: never repeated, but never eliminated as a potential alien transmission. I can easily imagine that a civilization might send out a one-shot broadcast rather than a continuous stream of signals. After all, that's what we did.

In 1974, scientists at the Arecibo Observatory sent a coded signal in the direction of the globular star cluster M13 for three minutes - and then just stopped. "It was really just a demo," Shostak said. It will take 25,000 years for the signal to reach M13, but once it arrives, the Arecibo signal might be as enigmatic for the aliens as the "Wow" signal is for us.

"If there is somebody on the other end, they're going to call it the 'Zork' signal, or whatever you want to call it," Shostak said. "They may puzzle over that for years."

Share your thoughts in the Forum

Share your thoughts in the Forum